You may have noticed that the Rocky Mountain region—especially if you moved here from either coast or the South—is notably lacking in broadleaf evergreens. That is because these evergreens are more prone to burn from both winter sun and wind—as well as to suffer winter water loss—than deciduous woody plants or needled evergreens. As a result, gardeners in our region must select and site such woody plants more thoughtfully than gardeners in other regions. Of course, what we call “Rocky Mountain” is really more like two regions: one that reliably retains winter snow cover, and one that does not. The three broadleaf evergreen natives described here, however, do well in a variety of gardens and exposures.

Learn more: How to Protect Broadleaf Evergreens from Winter Damage.

Siting Broadleaf Evergreens for Success

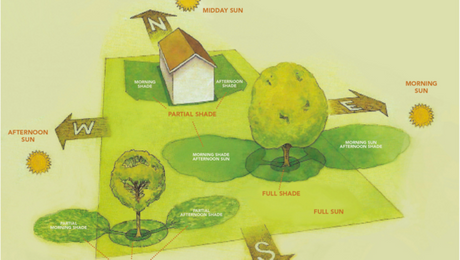

In winter-dry gardens, avoid siting broadleaf evergreens in locations that receive winter sun all day; the east face of a house, for example, is ideal. Winter snow cover reduces winter stress on evergreen plants, so gardens that retain snow cover can feature broadleaf evergreens in a greater diversity of sites with less work. Regardless, these sumptuous, structural garden additions add vibrance to our outdoor worlds when we appreciate it most and are worth the modest investment.

During establishment, irrigate all three of these plants regularly, and mulch with leaf, wood, or gravel mulch.

Rocky Mountain gardens that retain winter snow cover can host these plants in a variety of sites with relatively little winter upkeep.

Gardeners in snowless areas should site broadleaf evergreen plants where they receive a bit of shade in the afternoon. It is also a good idea to water them in winter.

|

|

Daphne

Daphne × burkwoodii ‘Carol Mackie’

Zones: 4–8

Size: 4 feet wide and 4 feet tall

One of our most striking broadleaf evergreens remains the classic ‘Carol Mackie’ daphne. With a superb branch structure and restrained growth that gives it a shapely form, it’s an easy choice for semi-formal gardens and tighter settings where large or ramble-prone woodies just won’t do. Teardrop-shape leaves with variegated edges just ooze taste, and come spring, the plant delights with an effusive bloom of four-petaled, soft-pink flowers. As if that isn’t enough, they’re fragrant—so deliciously so that a friend of mine insists on a ‘Carol Mackie’ specimen by the door everywhere they’ve lived, an insistence I wholeheartedly support. A few words for success on this one: Don’t plant ‘Carol Mackie’ in a clay that sits wet, and site thoughtfully; this shrub despises transplant. Hardy to Zone 4, the plants reach 4 feet high and wide in ideal conditions with age.

Littleleaf mountain mahogany

Cercocarpus ledifolius var. intricatus

Zones: 3–10

Size: 5 feet wide and 8 feet tall

This plant fits into a category we in horticulture sometimes call “workhorse” plants. They won’t dazzle with a flashy bloom or fragrance, and they won’t stop you at the nursery; they demonstrate their value in other ways—in this case, by sheer toughness. Littleleaf mountain mahogany doesn’t care what kind of soil it’s grown in, or how much it’s watered after establishment. In fact, this Cercocarpus will not thrive in a heavily irrigated, amended garden soil once established.

Taking an oval shape to around 5 feet, littleleaf mountain mahogany is a deer-proof (as much as any plant can be) plant that looks as good in January as it does in June. This fine-textured plant is xeric thanks to high-desert origins and is cold hardy, too, unfazed well into Zone 3. Unsurprisingly, it prefers full sun. Thanks to a dense, slow growth habit, it requires virtually no pruning, makes a good screen for an outdoor living space, and makes a good hiding space for local songbirds.

Manzanita

Arctostaphylos × coloradensis

Zones: 5–8

Size: 5 feet wide by 2 feet tall

An easy choice for gardens in Zone 5 and warmer, our native manzanitas have quickly become regional staples when it comes to tough and dapper shrub options. Reaching just over 2 feet tall with age, plants ramble to cover 4 or more feet across. They present with poise in the garden, adorned in unusually dark green, glossy leaves above beautiful, cinnamon-colored exfoliating bark. Thanks to precocious flowers, manzanitas provide a very early nectar source for flying insects. The attractive red berries formed on plants in this group are the source of the plant’s common name, which is Spanish for “little apple.” Be warned, however, that while these plants do fine on coarser soils, they do struggle in some clays. If you have clay soil but want to try growing a manzanita, consider a berm; that has done the trick for me.

| Bonus plant | |

|

|

Gardeners in regions much colder than Zone 5 should consider sticking to the extra cold-hardy parent of A. × coloradoensis, called Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (kinninnick or bearberry), which remains a ground cover but is hardy to Zone 2. |

See more native plants for the Mountain West

Native Tree Species for the Rocky Mountain Region

Native Shrubs That Do It All in the Mountain West

Native Annuals and Biennials for Rocky Mountain Gardens

Bryan Fischer lives and gardens at the intersection of the Great Plains and the Rockies. He is a horticulturist and the curator of plant collections for a local botanic garden.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in