Many gardens elicit a “Geez, how did they do this?” response. It is not because of massive hardscape or Versailles-level precision; rather, it is more of the sense that these gardens appear perfectly natural yet utterly artful, as though when walking through a nature preserve you had stumbled upon the perfect spot at the perfect time. But you are in a garden.

No type of garden evokes this kind of reaction like a naturalistic-style planting. You have probably seen such a design in a botanic garden, at the High Line in New York City, or in the pages of this magazine. Such gardens are lush, every space filled with plants knitting together like it all happened naturally—except it didn’t. Somebody designed that. And you can design one too.

Because they work with nature and not against it, these designs are ecologically sound and reduce maintenance for the gardener. They rely on a diversity of plants growing together, protecting the soil, and providing for other living things. This means no twines or stakes, fewer wheelbarrows of mulch, and no need to weed. A brief look at two approaches to naturalistic plantings will give you a sense of how you can create these designs, no matter what size your landscape.

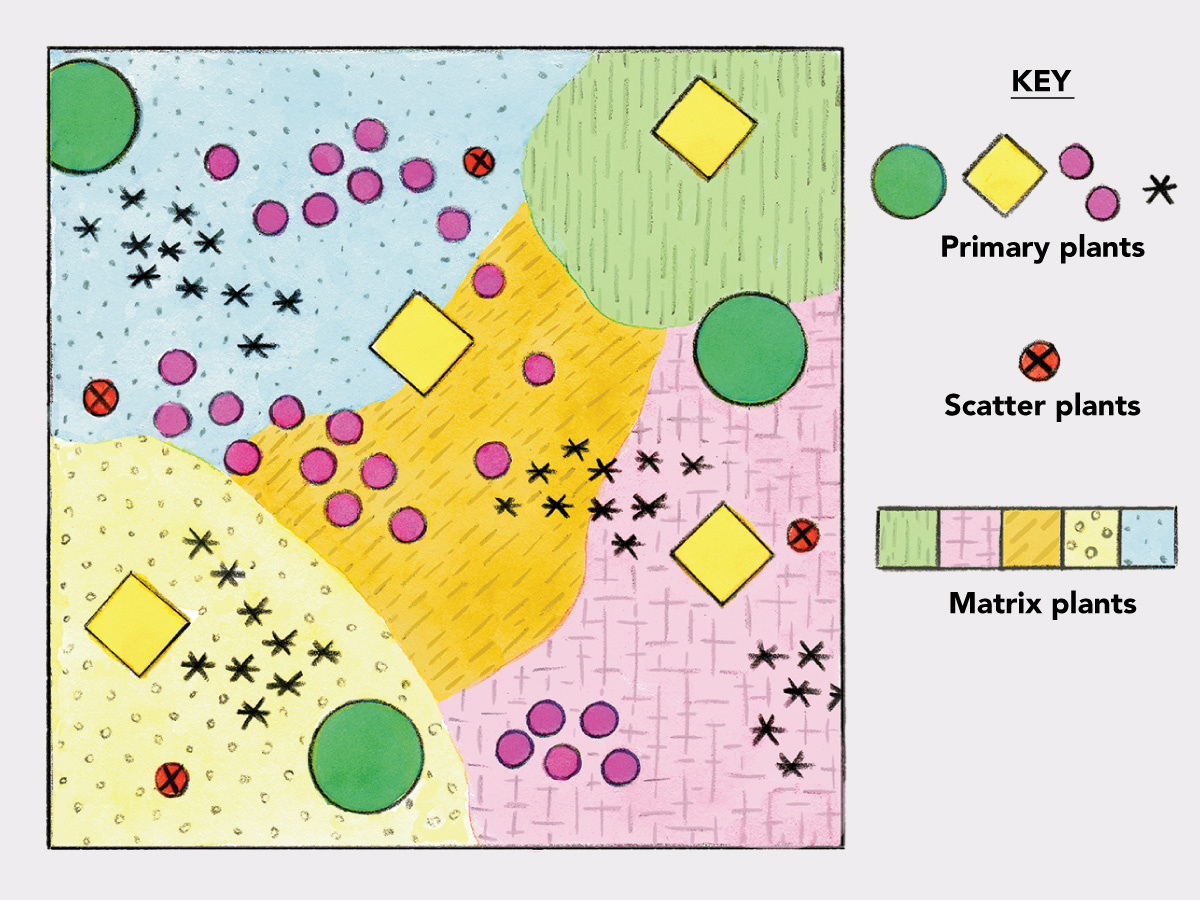

Design with three key plant types

One of the key principles in designing a naturalistic garden is understanding the roles certain plants play. In their book Planting: A New Perspective, Piet Oudolf and Noel Kingsbury define several essential kinds of plants.

First are “matrix plants.” A matrix is a foundational structure in which something else develops or is contained. Oudolf and Kingsbury use the analogy of a fruitcake, where the actual cake is considered the matrix that holds the fruit. Matrix plants, therefore, are masses of ground cover plants that form the underpinning of the design. If you hear “ground cover” and think of low-growing plants that spread quickly, you are only partly correct. A gardener has many opportunities to use plants in this role. A good matrix plant not only takes up space (thus limiting the opportunity for weeds to grow) but also doesn’t steal the show. Because these plants will be used in large numbers, their colors should be soft. Their forms should be muted in interest but always relatively tidy. Great options for creating a matrix are perennials such as bigroot geranium (Geranium macrorrhizum and cvs., Zones 4–8), epimedium (Epimedium spp. and cvs., Zones 4–9), and grasses that stay relatively small, such as sedges (Carex spp. and cvs., Zones 2–9) and autumn moor grass (Seslaria autumnalis, Zones 5–9).

Tip: Bulbs are a bright idea

Perhaps the unsung heroes of a naturalistic planting are bulbs. They provide seasonal structure and interest throughout the year and are especially valuable early on, when they appear and do their thing while the other plants bulk up. Then they disappear again until next year. Sprinkling them in randomly is easy, too, adding to the spontaneous, natural feel of a planting.

Of course, no fruitcake can work with just cake. It needs fruit. So to your matrix plants Oudolf and Kingsbury suggest adding “primary plants.” These plants are the most visually dominant in the design, relying mostly on color and form to provide multiple seasons of interest. Repeated throughout a planting, primary plants are used in a greater variety than matrix plants, with some taking charge as other primary plants start to fade in interest. May Night salvia (Salvia ‘Mainacht’, Zones 5–9), ‘Purple Smoke’ baptisia (Baptisia australis ‘Purple Smoke’, Zones 3–9), or ‘Frances Williams’ hosta (Hosta ‘Frances Williams’, Zones 3–9) are all great candidates.

Planting plan details |

The third kind of plant helps bring the whole design together. Dotted randomly throughout a design, “scatter plants” enhance the natural feel of a design. They should also add an extended period of structure or a jolt of seasonal color. Planted individually but repeated for unity and rhythm, plants like ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius and cvs., Zones 3–8), smokebush (Cotinus coggygria and cvs., Zones 4–9), or ‘Skyracer’ purple moor grass (Molinia caerulea subsp. caerulea ‘Skyracer’, Zones 5–9) can serve this purpose.

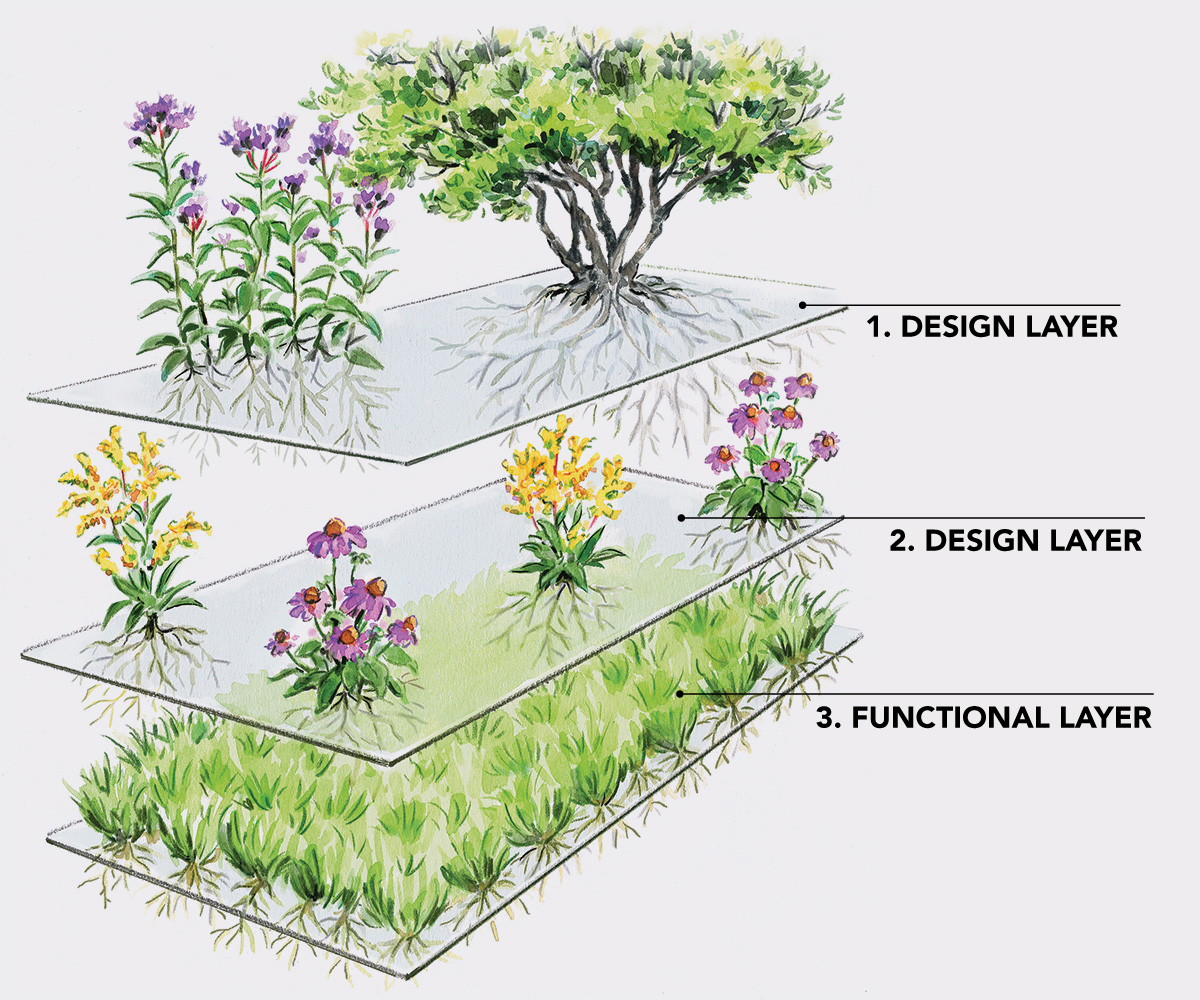

Another approach is to think in layers

In their book Planting in a Post-Wild World, Thomas Rainer and Claudia West offer another way to think about a naturalistic design. They encourage us to think in terms of layers when creating this type of planting: a design layer and a functional layer.

The main goal of the design layer is to provide aesthetic interest and a level of order or “legibility” so that people can relate to the planting in a more meaningful way than if it were just a wild tangle of plants. This layer is made up of two types of plants. Structural plants are large plants that make up the backbone of the design. These trees, shrubs, or tall perennials should have distinct shapes and year-round presence. Without these plants, the design will collapse. The second type of plant in the design layer are seasonal theme plants, whose visual dominance peaks at various times of the year. Their purpose is to heighten interest in the design, increase its legibility, and soften the structural plants they surround. The variety of seasonal theme plants should be such that certain plants create visual interest as others have finished their show.

Planting plan details1. Design layer: Structural plants These plants are the bones of the design, ensuring year-round presence. 2. Design layer: Seasonal theme plants Using a wide variety of plants with peaks at different times of the year ensures continued waves of interest. 3. Functional layer: Ground cover and filler plants This layer functions as a living mulch—one you don’t have to replenish yearly. |

The functional layer of a planting provides the ecological benefit, providing sustenance and shelter for insects, keeping down weeds, and protecting the soil. Similar to Oudolf’s matrix plants, these generally low-growing plants have soft shapes that weave around and under the design layer. “Use them like you would mulch,” Rainer and West recommend. By planting a diversity of genera and species of ground cover plants, you provide a greater benefit to a greater number of insects and wildlife. Also in this layer are what they call “filler plants.” These are short-lived, reseeding plants that can fill gaps, cover ground, and provide interest while the long-term players in the design get up to size.

The similarity in the approaches of the designers mentioned is easy to see, but there is much more to these concepts than we can get into here. If you are still a little intimidated to try them out for yourself, don’t be. A naturalistic design can be scaled to any size bed or landscape. Feel free to start small and expand from there—unless you enjoy hauling wheelbarrows full of mulch around.

More on naturalistic gardens:

- Plants for a Matrix-Style Garden

- Plants for a Layered-Style Garden

- Thomas Rainer and Piet Oudolf on Naturalistic Gardens

Steve Aitken is editor at large.

Photos, except where noted: Adam Woodruff

Illustrations: Elara Tanguy

Comments

You are right, now you need to think more about the environment than about yourself. After all, many projects that we love so much can harm the soil. I also recently read on the site https://featherlink.org/ about some problems and human activities that harm animals or birds

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in