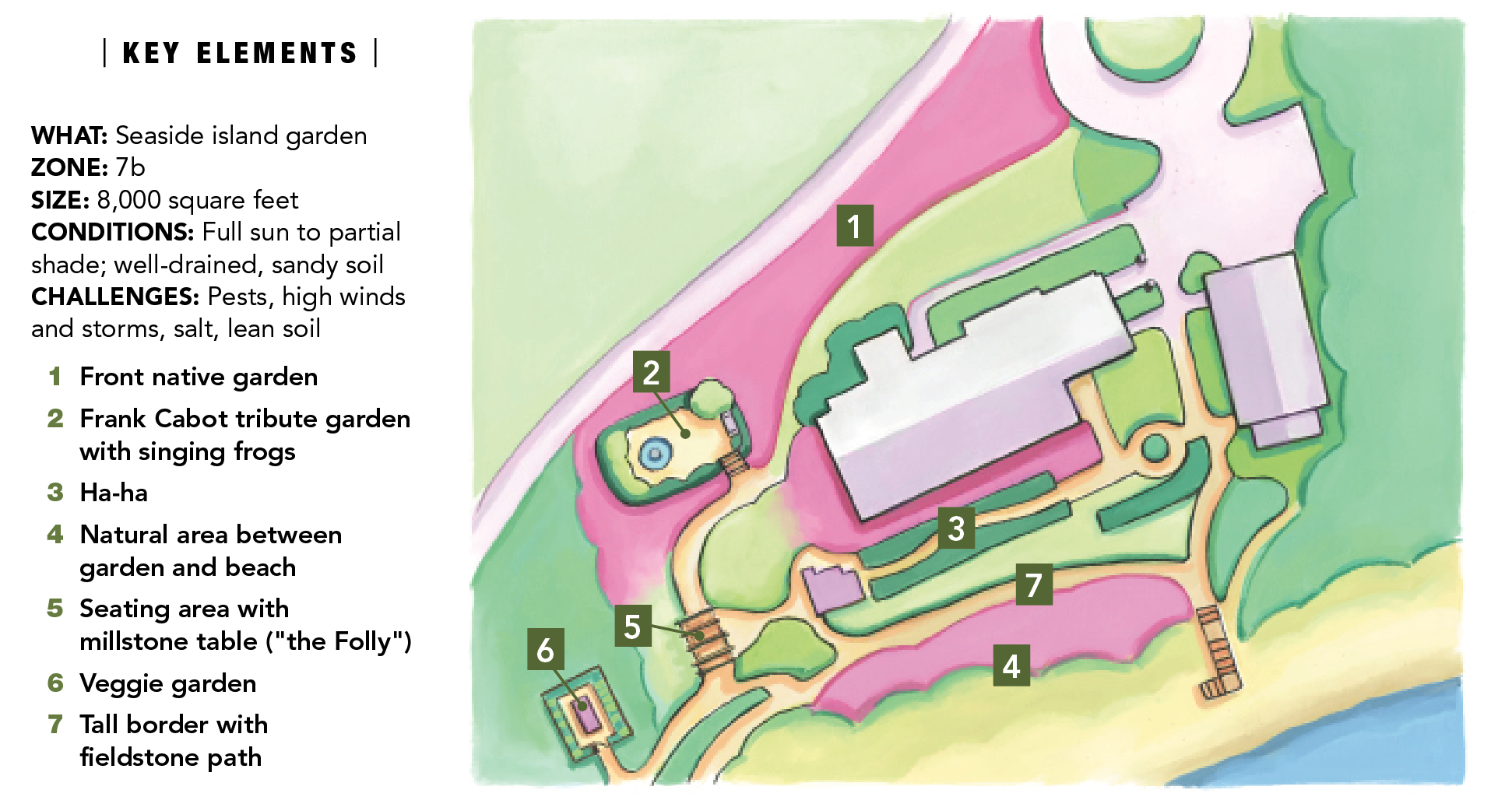

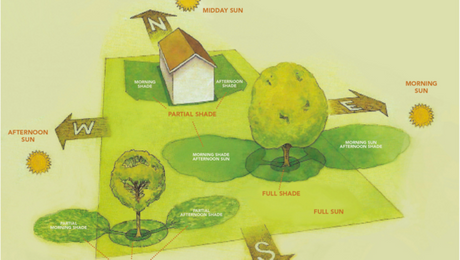

When Susan and Coleman Burke purchased land overlooking the bay on the Massachusetts island of Nantucket several decades ago, they were able to build their house and seaside garden from scratch. This blank slate presented them with enormous opportunities; however, they also had to contend with a number of challenges. The garden is right next to the beach, and the windy, salty air is difficult enough for plants on a good day, but it is potentially ruinous during storms. The soil is sandy and exposed to salt water, so using sea-loving plants was an absolute must. In addition, Nantucket is overrun with rabbits and deer (which were introduced to the island), since there are virtually no predators to keep their populations in check.

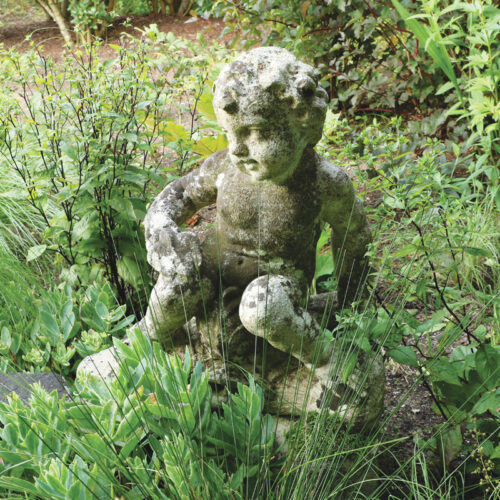

Susan and her longtime collaborator and landscape designer Julie Jordin have managed to work within these obstacles to create a unique garden. Layered beds with naturalistic hardscaping and antique ornamentation in the back of the garden contrast with the more formal area in the front. These beds and borders also transition seamlessly to the native flora that surrounds the space. I sat down with Susan and Julie while overlooking the sunset on the water to discuss their design process and techniques to keep the garden thriving.

This garden is right on the water. Are there any strategies you use to minimize damage from the elements?

Julie Jordin: We leave all of the plant foliage standing over winter to prevent desiccation of the soil to the plant crowns, as the winter winds are very dry. If you leave all those crowns exposed, they get too dried out and perish. We also selectively cut back or deadhead plants that may want to reseed aggressively, like plume poppy (Macleaya cordata, Zones 3–8) and rattlesnake master (Eryngium yuccifolium, Zones 4–9).

Susan Burke: Even with that we get tons of storm damage, and nearly everything can be affected.

JJ: Sometimes we’ll just lose whole crops of things. Last winter there was a –4°F cold snap following a 50°F week, and we lost all the butterfly bushes (Buddleia spp. and cvs., Zones 5–10), as well as some lavender (Lavandula spp. and cvs., Zones 4–10) and rough-leaved hydrangea (Hydrangea aspera, Zones 7–9). We were lucky with the roses (Rosa spp. and cvs., Zones 3–10), which survived.

What are some of the plants you’ve included that can stand up to the wind, salt, and storms?

JJ: Sea lavender has been a recent introduction. We also have cardoon (Cynara cardunculus, Zones 7–10), white fleeceflower (Persicaria polymorpha, Zones 5–9), sea holly (Eryngium maritimum, Zones 4–9), and rugosa rose (Rosa rugosa, Zones 3–9). But everything in the garden is chosen for that. And as a matter of fact, if you were to take most of these plants and put them into a more comfy, cozy garden on the mainland, they would just become monsters and thugs, and you wouldn’t like it. But here they live on the precipice of death.

SB: I have another garden in Bedford, New York, and plants that get very tall there are much shorter here. It’s funny to see the difference.

JJ: It enables us to choose things that are really tough, and they look controlled because it’s a balance between the environment and their aggressiveness.

Which garden pests do you deal with regularly, and what strategies do you use to mitigate pest damage?

JJ: Rabbits and deer are prevalent. They’ll eat anything if they’re hungry! We also have moles periodically. We protect for deer in the offseason when no one is in residence by using cages, fencing, and repellent. However, when the summer comes you have to take down the protective barriers, and the deer and rabbits find their way in. But by that time there’s so much growth and things are planted so densely that it’s hard to see the damage. It’s just that you have to give the garden a chance to get to that point. So, for example, we use chicken-wire cages when we first plant hollyhocks (Alcea spp. and cvs., Zones 3–9); otherwise the rabbits will eat them.

How do you safeguard the veggie garden?

JJ: It is completely protected. It’s basically a cage (photo below). It even has a ceiling, because we had a deer actually jump in and get stuck there.

SB: The outer edge is bluestone sunk into the ground, and the sides and top are chicken wire.

JJ: This prevents all pests from getting in; it even prevents birds from picking at the fruit and the seeds. Of course, we still fight the same insects that other vegetable gardeners fight.

There are more-natural areas near the beach and around the perimeter, so how do you transition from these areas to the garden itself?

SB: Nantucket requires that there be a buffer of untouched natural land between the property and the beach, so the garden needed to blend into that wild section.

JJ: We try to maintain the seaside buffer by continually protecting and replenishing the natural vegetation there. This helps maintain and enrich the coastal bank. We have also planted plugs of native grasses that blend into the rough (photo below). We use purple lovegrass in drifts along the back of the perennials and into the top of the primary dune. We also have little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium, Zones 3–9) up there and American beachgrass (Ammophila breviligulata, Zones 3–8). Little bluestem roots can grow very deep, which makes them a good stabilizer of the bank.

And the front garden is all natives, correct?

JJ: Yes. That garden was designed specifically by Susan when she built the house, and it has stayed almost to design for as long as I’ve known her, which is about 25 years. The area has summersweet (Clethra alnifolia, Zones 3–9) because of its beautiful fragrant flowers and late-summer show, as well as arrowwood viburnum, bayberry, and some grasses, among others. Inkberry (Ilex glabra, Zones 4–9) acts as the formal hedge in the front of the house.

How did you decide on the hardscaping, such as the materials making up the different paths?

JJ: Each area has its own set of guiding principles. The journey to the front door is formal and contrasts with the naturalistic plantings. It’s a running bond with bluestone and natural cleft slate. The ha-ha is created with fieldstone and reclaimed granite block. And the stairs are made of antique granite curbing, which creates an old-world feeling. The upper perennial border, on the other hand, is made with loose fieldstones that fade into nature (photo below). Susan has a great eye for design, and she did a lot of the hardscape planning and adding of ornamentation in this garden.

Yes, I have noticed that this garden contains an abundance of historic elements—for example, the statuary, millstones, columns, and wrought-iron fencing. Where did those items come from?

SB: We have a millstone table in the seating area under the arbor that I just love and also millstone steps in the front garden. I collect them. I founded something 28 years ago called the Antique Garden Furniture Show to benefit the New York Botanical Garden. So many of the pieces here and in my garden in Bedford I bought over the years from the show. In the front, we also have the frog statues. I got the idea from garden designer Frank Cabot. In his garden, when you walked into this long allée, you broke a light beam, and the frogs played music. I got the name of the sculptor from him and ordered three. The center one is my late husband playing the banjo. And then the two that flank it are my kids playing other instruments. When you walk into that area of the garden, which is surrounded by formal hedges, you break the light beam and you’re greeted by playful music.

One of the most important elements of a seaside garden is, of course, the sea. How did you decide to frame the views of the water?

SB: I asked our architect to build me a house like a ship so that I could have a view on both sides—the marsh on one side and the sound on the other. And so the windows in this house are situated on both sides so that you can see through 90% of the rooms in the house to the garden and the ocean.

JJ: Because of the siting of the property, the garden is nestled into the grade and doesn’t protrude; the dune beyond is higher than the garden and probably equal to the level of the first floor. So you can’t see the ocean at all when you are in the garden. However, you can see it from the back porch and from inside the house. And when you are looking out at the garden and the sea, the layers of the taller plants in the upper perennial border magically catch the western setting sunlight and illuminate the garden at the best part of the day.

| DESIGN IDEAS |

The benefits of a sunken garden

The ha-ha originated in England in the 18th century as a sunken fence that could give viewers the illusion of an uninterrupted landscape while providing a boundary for grazing livestock. It then began to be used in formal garden designs. Susan got the idea to install a ha-ha from garden designer Russell Page, who told her that in a good garden you should be able to discover new surprises as you walk throughout the space. This sunken area is abutted by the back garden on one side and the porch on the other (photo above). Not visible from the porch, the ha-ha can only be discovered by walking into the landscape. While honoring the spirit of discovery remains its main purpose, it does provide some benefits that the rest of the garden cannot:

Deterring pests. Since this part of the garden is sunken into the ground and gated, it’s harder for rabbits and deer to enter. However, over time they have become braver and occasionally find their way inside. But they tend not to stay as long as they do in other areas.

Windproofing. This area provides a break from the harsh sea winds; as a result, taller and more delicate plants that wouldn’t be able to thrive in other parts of the garden can do so here. These include hollyhocks, vines on tutors, and dahlias (Dahlia spp. and cvs., Zones 7–11).

Creating a microclimate. The ha-ha is somewhat moister and warmer than the rest of the garden due to the hardscaping and its being dug deeper into the earth. Meadowsweet (Filipendula cvs., Zones 3–9) can find a home in the wetter soil here, whereas it would struggle in the main garden.

New design opportunities. Because this area is a bit cut off from the rest of the landscape and has more-limited space, unusual and specimen plants such as martagon lilies (Lilium martagon cvs., Zones 3–9), mini hostas (Hosta cvs., Zones 3–9), and ‘Lilac Squirrel’ Korean burnet (Sanguisorba hakusanensis ‘Lilac Squirrel’, Zones 4–8) have their place to shine. Red flowers such as ‘Bishop of Llandaff’ dahlia, which would clash with the design of the main garden, are also used here.

| PLANT PICKS |

Good candidates for blurring boundary lines

In this garden that blends so seamlessly with the natural landscape surrounding it, certain plants are key players in shifting from the manicured beds to the wild flora. The following mostly native shrubs and perennials tolerate the challenging conditions well. They are equally at home in the garden and at its edges.

Beach plum

Name: Prunus maritima

Zones: 3–8

Size: 3 to 8 feet tall and 3 to 5 feet wide

Conditions: Full sun to partial shade; dry, well-drained soil

Native range: Northeast and Mid-Atlantic United States

This dense, suckering shrub blooms with a spray of white spring flowers that give way to fruits that are dark purple to red. These plums are beloved by wildlife.

Eastern sweetshrub

Name: Calycanthus floridus

Zones: 4–9

Size: 6 to 12 feet tall and wide

Conditions: Full sun to partial shade; well-drained soil

Native range: Southeastern United States

The super-glossy, rounded leaves of this woody plant are the perfect contrast to its late-spring and early-summer flowers, which are a dark maroon with strappy petals. This native is not plagued by any major diseases or pests and tolerates most soil types.

Arrowwood viburnum

Name: Viburnum dentatum

Zones: 3–8

Size: 6 to 10 feet tall and wide

Conditions: Full sun to partial shade; well-drained soil

Native range: Eastern United States

Arrowwood viburnum’s arching stems form a loose habit. This shrub looks good from spring to fall, with lacy umbel blooms turning to dark blue berries, which are punctuated by gorgeous yellow and red fall foliage.

Sea lavender

Name: Limonium latifolium

Zones: 4–9

Size: 1½ to 2½ feet tall and 2 to 2½ feet wide

Conditions: Full sun to partial shade; dry, well-drained soil

Native range: Southeastern Europe

Sea lavender is extremely salt tolerant and is rarely browsed by deer. Its light purple summer blooms float above its broad-leaved foliage and dance in the ocean breeze. As a bonus, the leaves transition to red as cool weather nears.

Northern bayberry

Name: Morella pensylvanica syn. Myrica pensylvanica

Zones: 3–7

Size: 5 to 8 feet tall and wide

Conditions: Full sun to partial shade; wet to dry soil

Native range: Eastern North America

The dense branching structure and attractive fragrant leaves of this deciduous to semi-evergreen shrub make it perfect for use as a hedge. White berries remain over winter to provide additional interest.

Purple lovegrass

Name: Eragrostis spectabilis

Zones: 4–9

Size: 1 to 2 feet tall and wide

Conditions: Full sun; average to dry, well-drained soil

Native range: Eastern and central North America

Sprays of purple-red inflorescences seem to completely cover the foliage of this grass when it blooms. Spreading slowly via rhizomes, it will form a nice mat over time.

Diana Koehm is the assistant editor. Susan Burke is a lifelong gardener who has been a trustee of the New York Botanical Garden for over 30 years. Julie Jordin is a garden designer and horticulturist who has blended artistry with ecology to build gardens in Nantucket and beyond since 1995.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in