If you’re the type of person who likes to learn about plant pests in your free time, odds are you have already heard or read about a group of organisms known as nematodes. Many nematodes are beneficial and used as biological control agents of specific pest organisms in agriculture. Others, however, are problematic parasites of animals and plants, such as the dog heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) and beech-leaf disease nematode (Litylenchus crenatae). One group of nematodes that should be kept on your radar are root-knot nematodes (any member of the genus Meloidogyne), which are common plant parasites.

The 411 on root-knot nematodes

Root-knot nematodes cause damage to a variety of crops and ornamental plants and can be found in temperate and tropical areas around the globe. Sometimes this damage can be severe and cause significant crop loss. Root-knot nematodes get their common name from the “knots,” the swellings or galls, that develop at their feeding sites on roots. The size of a swelling varies and depends on the host, the species of root-knot nematode, and the number of adult females within the gall.

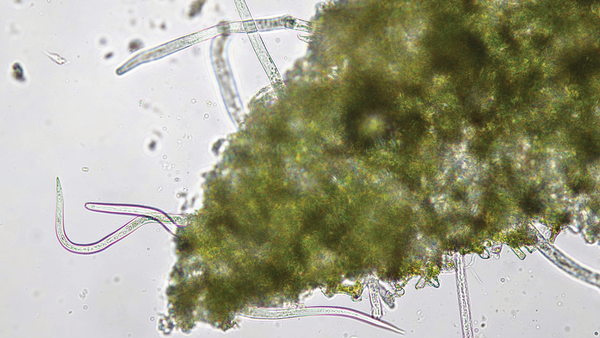

Adult female root-knot nematodes are sedentary, swollen, and cystlike, while the males and juveniles are motile and vermiform (wormlike). Adults range from 0.5 to 1.5 millimeters in length. Their numbers increase in step with the growth of the host plant, so they tend to be most abundant in summer when their hosts are growing vigorously. Root-knot nematodes move most easily in wet, sandy soil. This environment is most likely to result in significant nematode damage. In the South, plants that are grown in sand—such as golfing turf and peanuts—are commonly affected.

Besides the formation of root galls, there are other symptoms to look out for when scouting for root-knot nematodes. Aboveground parts of the plant often experience leaf chlorosis (yellowing), stunting (reduced growth), poor flower and fruit set, and mild wilting. Certain crops, such as carrots, develop misshapen, forked, or “hairy” roots, with a proliferation of secondary roots off the taproot. Keep in mind, however, that these symptoms can also be caused by rocky soil, fresh manure as a fertilizer source, or some root-rot pathogens. If you suspect a nematode infestation, have your plant tested by a local diagnostic clinic before moving forward with management.

Helpful tips on prevention and management

Advanced morphological or molecular identification is usually required to determine the species of root-knot nematode, but management recommendations tend to vary by crop type, not nematode species, with possible options including the use of nematicides.

If you receive confirmation of a root-knot nematode infestation, the best first step is to remove the infested plant(s) and those nearby as soon as practical and replant with a resistant alternate plant.

Marigolds (Tagetes spp. and cvs., annual) are often a great choice for replanting in an infected nematode area, as they produce an allelopathic compound called alpha-terthienyl. This chemical is toxic to other types of organisms, including nematodes, insects, and certain pathogenic fungi and bacteria, and can significantly suppress their growth. The University of Florida has a helpful guide for using marigolds to reduce nematode pressure. The guide includes a table at the very bottom of the document that provides a list of various marigold cultivars and their resistance to nematode damage.

If you would like to return to your original plant, whether or not you plan to apply nematicides, allow the marigolds to grow for at least a full year (preferably longer), then remove them and replace them with your desired plant. If you can do a three-crop rotation, ornamental grasses (landscapes) or grass cover crops (commercial/agricultural) are a good second-season choice, as they often tolerate difficult soil and have few problems with nematodes. To use pachysandra (Pachysandra spp. and cvs., Zones 4–9) as an example “root-knot-susceptible” plant, consider rotating from pachysandra to marigold to grass to pachysandra or pachysandra to marigold to grass to marigold to pachysandra. (The two rotations of marigold in the second option will be particularly helpful if you do not plan to also use a nematicide.)

When you remove your original plant, this will be a convenient time for you to make any necessary soil amendments. Root-knot nematodes prefer wet, sandy, acidic soil, so making any adjustments to avoid that environment will likely help reduce nematode pressure. Additionally, the period between removal and planting is a convenient time to have the area treated with a nematicide. Some nematicides, such as Azadirachtin, are more effective if lime is applied immediately afterward. Note that certain organic nematicides derived from black walnut (5-hydroxy-1,4-naphthalenedione, aka juglone) may cause reduced performance of plants grown in the area immediately after application, so use with caution.

Remember to always wear protective equipment and to carefully follow the instructions on the label of a product. Some products will need to be purchased and applied by a certified professional. Ensure that root-knot nematodes (which may sometimes be listed as simply “Meloidogyne,” “soil-borne nematodes,” or “root-feeding nematodes”) are managed with the product you use, and apply it at appropriate rates.

—Nicholas Goltz, DPM, is a plant pathologist and extension educator in the northeastern United States, where he helps growers and homeowners find holistic and comprehensive solutions for plant problems.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in