Earth-Friendly Containers

Most of the pots we buy, use, and discard are made of single-use materials. Is there a sustainable solution?

The dirty secret of gardening is that there is an aspect of the hobby that is terrible for the environment—namely, the plastic pots that dominate the nursery industry. It’s a touchy subject that most of us think about but quickly push aside because it’s such an inconvenient truth. We’re gardening, in part, to better the environment, but do the ends justify the means? Many of the pots that house the plants we buy are made of single-use materials. If we’re interested in being more earth friendly, we need to look for a sustainable solution.

How has plastic become such a problem?

For many years, the gardening industry has relied almost exclusively on plastic containers because of their durability, superior function, and low cost, as well as the wide variety of available sizes and shapes that make for easy shipping and marketing. However, we are now realizing that conventional plastics come with a lot of problems.

Plastics are derived from an array of materials, including crude oil. Since oil isn’t a renewable resource, plastic as a product isn’t environmentally friendly. As the use of plastics has increased, the volume being thrown away has increased, and in turn, the cost of solid waste collection has increased. But beyond higher costs being passed along to the consumer, plastics in landfills pose a contamination threat to water and soil. As plastic breaks down, it releases toxins that can contaminate the surrounding area.

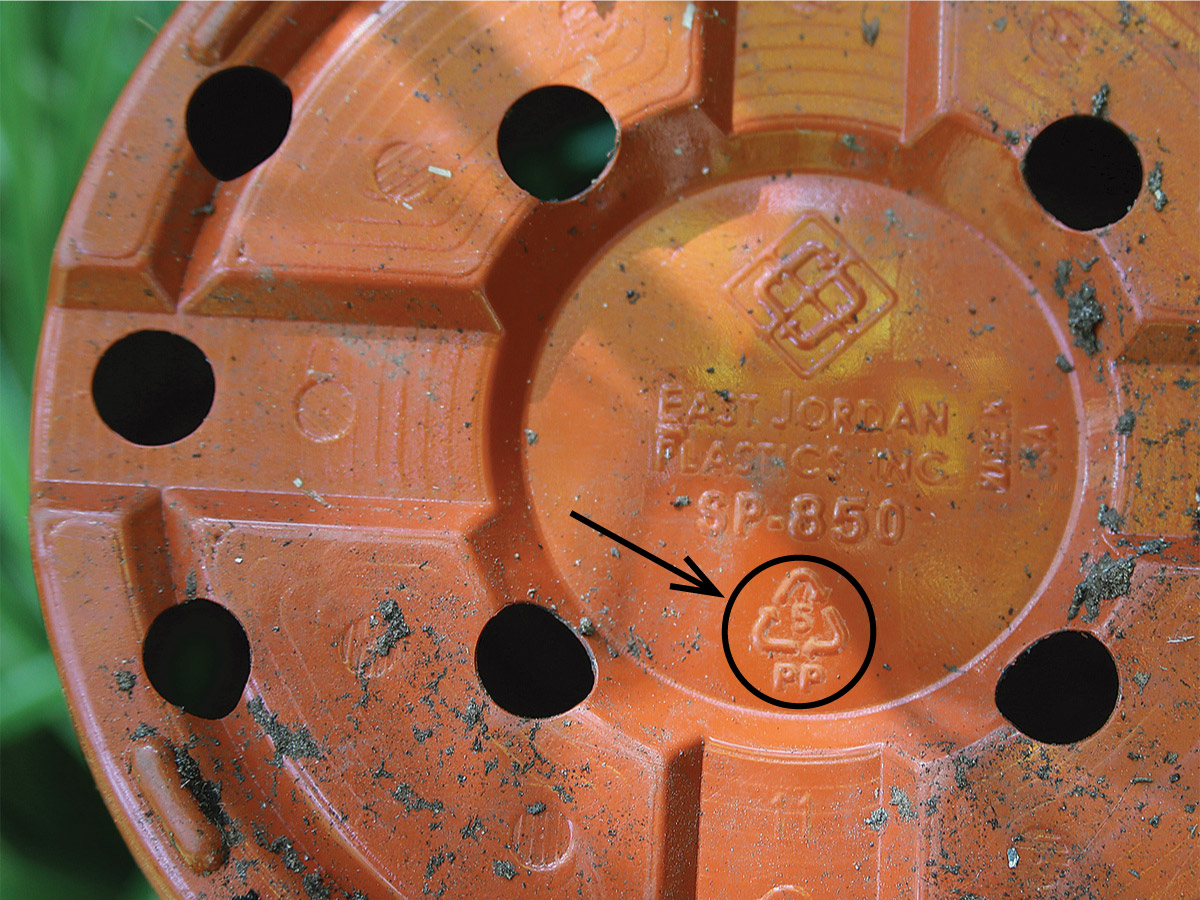

But what about recycling? Although numerous plastic recycling programs exist across the country, we still don’t take full advantage of them. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency reported that the rate of plastic waste recycling was only 9.1% in 2015. Many gardeners see this lack of recycling and assume that the types of plastic used in nursery pots—which can be identified by checking their recycling number—make them unrecyclable, but that is not the case. Most pots can, in fact, be recycled.

However, strong efforts by the green industry to encourage recycling haven’t yielded much. In order for plastic nursery containers to be recycled, they must be collected from gardeners, sorted by type, thoroughly washed to remove any debris, and then shipped to specific recycling facilities. And although modern recycling facilities can handle a wide variety of plastics—nursery pots included—they aren’t widespread, and finding one can be difficult. A certain town might have a facility that can handle one type of plastic, whereas the facility in the next town over can’t do the same.

Are there sustainable options?

There is now a wide variety of biodegradable containers to choose from made of animal- and plant-based by-products, including bioplastic, coir, poultry feathers, processed cow manure, paper fibers, and rice hulls. These containers offer an alternative to the standard plastic nursery container and reduce landfill waste because they decompose more rapidly than traditional plastic options.

Biodegradable containers are considered either compostable or plantable. Plantable containers are highly porous and can be placed (along with your plant) directly into the soil. Once they are in the soil, these containers degrade over time through a natural process in which soil microorganisms break down large and complex organic materials. Think about what happens to an organic soil amendment such as bark; it disappears over time, which is the same process. Compostable containers, on the other hand, must be removed before planting and placed in a compost pile for degradation to occur, again, by natural processes, over a longer period of time.

Once manufacturers started coming up with alternative containers, researchers across the globe began studying their performance under production conditions and making comparisons with the standard plastic container. To be considered viable alternatives, these biodegradable containers—or biocontainers—needed to show that they could be visually appealing (not crumbling and falling part) and house a healthy plant. Studies published by HortTechnology and other scientific journals show that plants produced in biocontainers have excellent growth in the greenhouse or nursery and also in the garden. These same studies show that plants grown in alternative containers have strong roots, good top growth, and plenty of blooms—and in many cases perform better than plants grown in conventional plastic containers.

Why not switch to all biocontainers?

On the flip side, three issues with biocontainers have surfaced: container integrity, price, and compatibility with existing production systems. The alternative containers must maintain their shape and form not only while on the greenhouse bench but also in gardeners’ hands. They must look good; if they don’t, that can negatively affect their marketability—which plant sellers will not tolerate. Alternative containers also tend to be more expensive compared to conventional plastic ones, and any cost added to production will either raise the price at the consumer end or reduce profits for the grower. And if producers cannot readily integrate alternative containers into their existing production systems—for example, a transplanting machine that has been designed to work with plastic containers—making the switch will be undesirable.

Researchers have found that introducing biocontainers carries a high level of risk and uncertainty for the green industry. The housing crisis of 2009–2010 substantially lowered the homeownership rate, causing a decline in demand for green industry products and services and consequently caused a loss of profits. Such developments might have slowed the interest in and the adoption of these new, unfamiliar products, especially if they require that a buyer pay a premium.

Recent market research from the Journal of Environmental Horticulture, however, indicates that gardeners are willing to pay more for nonplastic and recyclable containers, which is a good first step in making a systemic change. Other studies show that gardeners may be largely unaware that plants grown in alternative containers can be just as good—if not better—than those grown in plastic. Armed with this knowledge, gardeners may need to ask garden centers to increase their biocontainer offerings, which will create the demand that will encourage the green industry as a whole to widen its use of environmentally friendly pots.

See what you need to know about biodegradable containers.

Bodie Pennisi is a professor and researcher at the College of Agriculture at the University of Georgia. She is also a statewide extension landscape specialist and has studied the plant industry for years.

Photos (except where noted): courtesy of Bodie Pennisi

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in