The Rocky Mountain Region is stretched over 10,000 feet in elevation change and nearly over the full longitude of the Continental United States. Within this massive spread fit more than six biomes, ranging from the grasslands and prairie edges of northern New Mexico to the alpine of Montana. Despite the impressive diversity in soil and climate, many people in the area garden on our region’s namesake: rocks.

Often, rocky soils are quite young. Their presence indicates that not enough time has passed to weather parent materials (yes, rocks) into the complex that is soil. I often see gardeners trying to shoehorn leafy, traditional garden plants into these indisputably western landscapes. A better tactic, however, is embracing flora already adapted to such areas, which offers a simpler and less labor-intensive solution.

Rocky Mountain beardtongue

Name: Penstemon strictus

Zones: 4–9

Size: 24 to 30 inches tall and 36 inches wide

Conditions: Full to partial sun; well-drained soil

Native range: Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona

Among regionally adapted plants, a few groups stand out as obvious choices. With more than 250 species recognized, there is a penstemon for every garden—especially those with gravelly soils. These plants abhor the competition encouraged by richer media. Your part of the Rockies likely already has its own suite of these gorgeous plants that will be well-suited to your garden. If you speak to a local garden center or consult a regional wildflower book, they can help you find these species.

If a deep dive into the species isn’t to your taste, consider growing Rocky Mountain beardtongue. This penstemon blooms in early summer. You can expect numerous 2-foot royal purple or cerulean blue spikes of tube-shaped flowers above shiny green leaves.

These plants bloom hard with relatively few resources—so hard, in fact, that they will often “bloom themselves to death.” This means they will emphasize production of seeds over the longevity of the mother plant unless a knowledgeable gardener intervenes.

To ensure longevity, I deadhead my plants as their bloom finishes, leaving only one or two flower spikes to produce seed. This helps my beardtongue to redirect energy back into the mother plant. This not only ensures that the plant is longer lived, but it also allows for more modest seed production. ‘Rocky Mountain’ is an easy self-seeder, and a gravel mulch makes an ideal seedbed. With proper care, you will have a stand of penstemons for years to come.

Sulfur buckwheat

Name: Eriogonum umbellatum

Zones: 3–8

Size: 6 to 12 inches tall and 1 to 3 feet wide

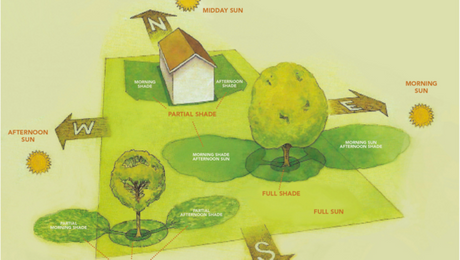

Conditions: Full sun to partial shade; well-drained soil

Native range: British Columbia and Alberta south to southern California, Arizona and eastern Colorado

A tasteful complement to the exuberant Rocky Mountain penstemon is the equally tough members of the genus Eriogonum. Considerably longer-lived, our native buckwheats don’t crumble under pressure and are one of only two genera native to the country that are more diverse than Penstemon.

If scouting out your local flavors isn’t to your taste this year, consider sulfur buckwheat, a species that’s hardy to USDA Zone 3 and sometimes referred to as sulfur flower.

Sulfur buckwheat grows as a low mat of attractive foliage that often colors red in winter. These tiny toughies relish poor sites and put on a delightful show of acid-yellow pom-pom-type flowers held on stiff, 6-inch stems. As the weeks go by, those flowers give way to papery clusters of red-blushed seeds.

Cliff fendlerbush

Name: Fendlera rupicola

Zones: 6–8

Size: 2 to 4 feet wide, 4 to 10 feet tall

Conditions: Full sun to partial shade; well-drained soil, caliche, clay

Native range: Colorado, Texas, Arizona, northern Mexico

Considerably larger than the previous two plants, Fendlera rupicola is right at home in rocky soil—so much so that both its common name, cliff fendlerbush, and its species name (“rupicola,” which translates to “of rocky places”) reference how it has a penchant for setting up shop in what many would hardly consider soil.

These large shrubs produce an abundance of slender stems, gradually taking a vase or rounded shape to 6 feet, but sometimes higher. In spring, pink-white, pearly buds pop and reveal fragrant, wedding-white, four-petaled flowers along the entire height of the shrub.

Plants flower on old wood and are slow to establish, so be patient when planting cliff fendlerbush. I prune my specimen lightly during late winter. However, if it’s looking particularly rangy, I will rejuvenate prune it back to its base and accept losing a couple years’ worth of flowers.

As with many of my articles, you may notice a theme in this piece: Tuning your plant palette to your site through the inclusion of site-adapted plants rather than site modification presents a less laborious, more environmentally friendly route to improve your gardening.

In this instance, the use of appropriate mulches (often this means gravel) and the inclusion of plants that love these lean, harsh sites will save you time and effort in the long run. Just be sure to water adequately through establishing and protecting your transplants from browsing wildlife. Tender transplants are often the tastiest morsels around.

See more native plants for the Mountain West

Native Tree Species for the Rocky Mountain Region

Native Shrubs That Do It All in the Mountain West

Native Annuals and Biennials for Rocky Mountain Gardens

Bryan Fischer lives and gardens at the intersection of the Great Plains and the Rockies. He is a horticulturist and the curator of plant collections for a local botanic garden.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in